Why Collect First Editions?

Even if you're brand new to the world of antiquarian books, you've undoubtedly noticed that first editions are the trade's gold standard. Indeed, first editions often fetch much higher prices than later editions, even if the books seem exactly the same to the untrained collector. But as you build your rare book collection, you can't afford not to collect first editions.

Scarcity

Publishing a book requires taking a calculated risk. What if the book gets panned by the critics? Or what if it simply languishes undiscovered, receiving neither critical acclaim nor derision? To mitigate this risk, publishers often choose to publish a book in only small numbers at first, and then issue reprints if the title proves commercially viable. Thus first editions are often available in much more limited numbers than subsequent editions. This is especially true for authors' first works, because they have no reputation of literary success.

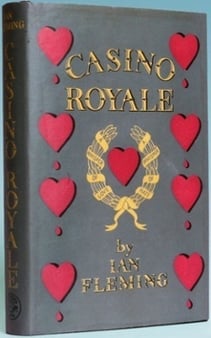

And in the world of collecting, scarcity generally increases value. The more difficult it is to find a book, the higher the price will be (presuming that the book is a desirable title). Ian Fleming's Casino Royale is an excellent example; only 4,728 copies of the book were published in the first UK run (April 1953). The book marked the start of Fleming's incredibly popular James Bond series, and it has been adapted for the silver screen three times. Less than 3,000 copies of this first edition are thought to survive. Thanks to the book's popularity, and the scarcity of first editions in the market, a fine first edition of Casino Royale easily costs more than $30,000. Browse Ian Fleming Books>>

Author's Intent

Generally authors are quite involved in the publication process. Therefore the first edition of a book often represents the version that's closest to an author's original intentions. We find a classic illustration of this idea with Ray Bradbury and Farenheit 451. In the Afterword to a much later edition of his famous novel, Bradbury writes, "Only six weeks ago I discovered tha, over the years, some cubby-hole editors at Ballantine Books, fearful of contaminating the young, had, bit by bit, censored some 75 separate sections from the novel." The differences, then, between the first edition and subsequent ones truly represent a departure from Bradbury's concept of the book.

The opposite may also be true. Consider Charles Dickens' Great Expectations. The first edition, published in 1861 has one ending, which is quite melancholy. When Dickens' colleague and confidant Edward Bulwer-Lytton read the manuscript, however, he urged Dickens to change the ending. Dickens complied, and the 1862 edition got a new ending. In this instance, serious collectors would strive to attain both the 1861 and the 1862 editions of Great Expectations. Dickens was certainly not the only author to change his work between publishing runs--Henry James, for instance, was notorious for changing his works between print runs.

Resources for Collecting First Editions

Even if you're a novice collector of rare books, you've undoubtedly heard about the importance of identifying first editions. Generally first editions were printed in smaller numbers, making them more scarce. Furthermore, there's a certain allure to having the "very first" of something. Because first edition identification is critical to building a rare book collection, it's important to invest in at least a few useful resources.

Pocket Guide to the Identification of First Editions

Compiled by Bill McBride, Pocket Guide to the Identification of First Editions is indispensable when you're browsing at book fairs, garage sales, or antique stores. It lists the methods that English-language publishers have used to identify first editions, both hardbound and paperbound, past and present. As there are myriad ways to indicate a book's edition, and each publisher's method has its own nuances, you'll often see even the most seasoned book dealers consulting the Pocket Guide on occasion.

First Editions: A Guide to Identification

Edited by Edward N Zempel and Linda A Verkler, the fourth edition of First Editions: A Guide to Identification is much more than a handy pocket guide. It's a comprehensive guide to the first edition identification statements of selected North American, British Commonwealth, and Irish publishers. First Editions includes only information obtained directly from the publishers themselves, "from the horse's mouth" as it were. It holds all the statements from the first, second, and third editions of HS Boutell's First Editions of To-day and How to Tell Them (1928, 1937, and 1949) along with those from A First Edition? (1977) and previous editions of First Editions: A Guide to Identification (1984, 1989, and 1995).

Relevant Bibliographies

Note that these first edition guides primarily focus on books published in the twentieth century and later. They also don't offer guidance on differentiating, for instance, between the first state and later states of a book--both of which may still be considered first editions. And some desirable editions of books will be published by small presses--which aren't included in standard resources. That's why it's critical to obtain a bibliography for your area of focus. For instance, collectors of Charles van Sandwyk rely on the Interim Bibliography published by Heavenly Monkey in 2000. Nowhere else will you find information about identifying van Sandwyk's first editions, and this bibliography is a collector's item unto itself.

Bibliographies can also address broader subjects. Jacob Blanck's Bibliography of American Literature represents a definitive resource, and you'll frequently find references to "BAL" in book dealers' descriptions. It's a truly exhaustive work, published in multiple volumes by Oak Knoll Press. Some collectors obtain only the volumes that contain information on the authors that interest them, while others get the entire set.

You'll also find much more specialized bibliographies, such as Bibliotheca Mechanica by Verne L Roberts and Ivy Trent, considered the authoritative bibliography on early engineering and mechanics. A Matter of Taste, a comprehensive bibliography of the international collection of books on food and drink housed at the Lilly Library at Indiana University. It includes books on gastronomy, wine making, and a number of other topics relevant to collectors of antiquarian cookery books. Just about every area of specialization has its own bibliography.

A New Generation of Collectors' Resources

The ubiquity of the internet has substantially changed the world of rare book collecting. There's a wealth of information available to collectors on the internet, including our own library of downloadable guides. In our resource library, you'll find guides on rare book care and restoration, along with collector's checklists for Newbery- and Caldecott-winning books, guides for collecting first editions from modern publishers, and much more!

Identifying First Editions

Changes like a different ending are relatively easy to identify. But often it is more difficult to identify first editions. Books published before 1900 often don't bear any written indication about whether a book is a first edition or later one. So collectors rely on points of issue, that is, differences between the first edition and subsequent ones. Common points of issue include the following:

- Textual differences: It's common to correct typographical errors from the first edition, for instance. Or, as we mentioned above, the author may make more substantial changes to the text.

- Materials used: The first edition may be bound in a different fabric, or the later editions might be printed on a different (usually less expensive) paper.

- Format: The first edition may contain more or fewer pages than the later edition. It could also lack a foreword, afterword, or other ancillary materials that are added later.

It's also important to understand the difference between first issue and first state. A point of issue refers to a change made after copies of the book already entered circulation. Differences in state occur when changes are made to a book before any copies are circulated. For example, if a publisher identifies a typographical error during the initial printing process, it may be corrected mid-print. (This was much more common in the days when books were still printed manually using moveable type.) So books that are first edition/first state would contain the error, while first edition/second state copies would lack the error.

After about 1900, many major publishing houses started adopting conventions for identifying first editions.

Identifying First Editions From Different Publishing Houses

Alfred A. Knopf

If you collect rare books, identifying first editions is an important skill. Each publisher has developed its own own conventions for denoting first editions/first printings. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. is an excellent example of a publishing house whose style of indicating first editions has stayed relatively consistent over the years, which isn't always the case.

Alfred and Blanche Knopf

Alfred and Blanche Knopf founded Alfred A. Knopf in 1915 and incorporated three years later. Alfred served as president, while Blanche was vice president. The couple traveled extensively, soon earning a reputation for publishing not only excellent American writers, but also authors from Europe, Asia, and Latin America. To date, their roster of authors includes nearly 50 Pulitzer Prize winners and more than 15 Nobel laureates.

In 1923, Knopf began publishing periodicals. The first, The American Mercury, published some of the most influential writers of the 1920s and 1930s. Knopf published the magazine until 1934. Meanwhile Borzoi Quarterly came into existence as a means for promoting new books. The borzoi has always been the icon of the publishing house. Random House acquired Knopf in 1960, and it is now part of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group at Random House.

How to Spot the First Printing of an Alfred A. Knopf First Edition

Publishers generally issue statements about how they indicate first editions. Alfred A. Knopf is no exception; the house has issued a total of nine statements since 1928.

Alfred A. Knopf, Inc

1915-1933: For each printing after the first, the words "Second Printing," "Third Printing," etc. are listed on the copyright page. The first printing is not indicated in this way. Books reprinted before publication date include a note such as "First and second printings before publication" on the copyright page.

1933/1934-1947: During this time, Knopf transitioned to include more information on the copyright page of first editions. The changes were outlined in their 1936 statement. They began including the words "First Edition" or "First American Edition" on the copyright page where applicable. The latter was used only when the book had already been published abroad (regardless of the language used for publication).

Subsequent statements have reiterated that Knopf has not changed its identification methods for first editions. The 2000 statement added that Knopf was now a division of Random House, Inc, rather than its own corporation.

Alfred Knopf, Inc (United Kingdom)

The English house, which was discontinued in 1930, followed a different convention. They would place the month and year of first publication on the verso of the title page. Further impressions include the impression number and further editions by the edition number.

Now that you know how to identify their first editions, find more than thousand Alfred Knopf publications, including first editions of Nobel Laureates like Gabriel García Márquez or Toni Morrison, vampire novels of Anne Rice, presidential bibliographies by US presidents, cook books by Julia Child.

Doubleday

Since its inception in 1897, Doubleday has been a powerful presence in the American publishing landscape. Collectors often encounter books from the publishing house, so it's useful to know a bit about Doubleday's history and how to identify its first editions.

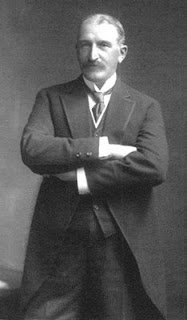

An Early Start in Publishing

Brooklyn native Frank Nelson Doubleday developed a love for publishing at an early age. By the time he was ten years old, he had already saved up money to purchase his own printing press. To recoup the cost, Doubleday sold advertisement space in the news circulars he printed.

Brooklyn native Frank Nelson Doubleday developed a love for publishing at an early age. By the time he was ten years old, he had already saved up money to purchase his own printing press. To recoup the cost, Doubleday sold advertisement space in the news circulars he printed.

Doubleday's father was a hatter, and when his business failed, Doubleday was forced to leave school and find a job. He was only fourteen years old. Doubleday's love for publishing led him to Charles Scribner's Sons, where he started out making $3 per week. Eighteen years later, Doubleday was still there, working as the publisher of Scribner's Magazine and as head of the subscription book division.

But by 1897, Doubleday's relationship with Charles Scribner's Sons had headed south, and he was ready for a change. He partnered with magazine publisher Samuel McClure to start the Doubleday and McClure Company. The following year, at the urging of banker John Pierpont Morgan, Doubleday and McClure accepted a contract to manage Harper and Brothers. Doubleday immediately delved into the company's records, only to find its finances in shambles. Between the Panic of 1893 and the extension of copyright law to foreign authors (legislation that Charles Dickens had fought so hard for!), Harper and Brother's was struggling. Ultimately, Doubleday, McClure, and Morgan decided to call the deal off.

New Leadership for a New Era

That failed business venture and other issues had put significant strain on the relationship between Doubleday and McClure. Thus, on December 31, 1899, the two dissolved their partnership. Doubleday invited Walter Hines Page, of The Atlantic Monthly, to join him and changed the firm's name to Doubleday, Page and Company. Page would remain with the organization until 1916, when he was named U.S. Ambassador to Great Britain.

In 1921, British publisher William Heinemann passed away unexpectedly without leaving an heir. Doubleday bought a controlling interest in his publishing business, knowing that it would be advantageous to expand his influence to the British publishing world. Ever the anglophile, Doubleday developed close friendships with a number of prominent authors and publishers, most notably Rudyard Kipling, whose The Day's Work was one of Doubleday's first bestsellers. It was Kipling who gave Doubleday his nickname, "Effendi," from his initials, "FND." Doubleday would also become close with Mark Twain, James Barrie, Alfred Harcourt, and others. After meeting John D. Rockefeller, Doubleday was asked to contribute to the magnate's autobiography, though it's not certain whether he ghostwrote the book or merely edited it.

Becoming a Giant in Modern Publishing

Doubleday, Page and Company merged with the George H. Doran Company in 1927. They became Doubleday, Doran and Company—and the largest publishing house in the English-speaking world. Almost twenty years later, in 1946, the firm became Doubleday and Company. Nelson Doubleday stepped aside as president and CEO, but he remained Chairman of the Board until he died in January, 1949.

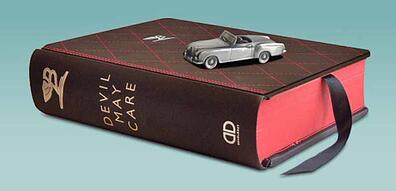

Doubleday published the Limited Bentley Edition of Sebastian Faulks' Devil May Care

In 1986, Doubleday, Duran and Company was sold to Bertelsmann. Two years later, it became part of Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing House. In 1998, it became a division of Random House. Then at the end of 2008, Doubleday merged with the Knopf Publishing Group, to form the Doubleday Knopf Publishing Group.

Identifying Doubleday First Editions

Doubleday has issued the following statements regarding the identification of its first editions:

- 1927-2000: The words "first edition" appear underneath the copyright notice, which can be found on the back of the title page. The year when the publishing house began to follow this convention is unknown.

- 2001: Following Doubleday's merger with Random House, the previous convention still applies, with one exception. The printline is included on the first print as well. Subsequent printings omit "first edition" and include an updated print line.

Doubleday (United Kingdom)

According to their 2001 statement, the publishing house follows the convention of Transworld Publishers, Ltd (United Kingdom): the lowest number in the number line indicates the printing. That practice applies to all the publishing house's imprints, such as Bantam, Black Swan, Corgi, and Doubleday.

Doubleday (Australia)

In 2000, Transworld Publishers merged with Random House Australia Pty Ltd, but retained two separate publishing divisions. Both essentially state the year when a title is initially published and subsequent editions. Both divisions also indicate impressions with a printline at the bottom of the copyright page (numbers 10 through 1). The smallest number is deleted with each reprint.

Grosset & Dunlap

Although publishers Grosset & Dunlap focused primarily on reprints, they did produce first editions. For book collectors, first edition identification is a vital skill. More often than not, conventions for distinguishing first editions vary from publishing house to publishing house. Take a moment to learn more about the history of Grosset & Dunlap and find out how to identify their first editions.

A Brief History

George T. Dunlap and Alexander Grosset began Grosset & Dunlap in 1898. The two men founded the publishing house on the premise that books should be inexpensive, accessible items in a time when many publishers were producing expensive volumes. Their laudable idea was tarnished by the fact that the publishers founded their business on piracy—in their early years, they reprinted existing books (without authorization) in order to avoid paying royalties.

From their inception, Grosset & Dunlap operated largely—although not exclusively—in reprints. They would also buy paperbacks in bulk, rebind them in cloth, and sell them at higher prices. Eventually other publishing houses began intentionally printing too many books with the express intention of selling the excess to Grosset & Dunlap.

However, Grosset & Dunlap did print original books, most notably the Nancy Drew, Hardy Boys, Bobbsey Twins, and Lone Ranger series. They were also famous for their photoplays, including that for King Kong. Many of their most famous books were produced in partnership with the Stratemeyer Syndicate. In 1979, the Stratemeyer Syndicate opted to work instead with Simon & Schuster, inspiring a long court dispute over the publishing rights of previously printed texts. Grosset & Dunlap won the right to continue printing existing books, especially the heavily disputed Hardy Boys series.

In 1982, Grosset & Dunlap was acquired by G. P. Putnam’s Sons and now they are owned by Penguin Random House.

Identifying First Editions

First edition identification for Grosset & Dunlap conforms to that of The Putnam & Grosset Group. First editions are not explicitly specified but must instead be surmised through the publication date on the copyright notice. Subsequent printings are also unspecified. If reprintings include new copyrighted material, there will be a new copyright date as well as the original copyright year.

Some books include a print code in letters or numbers in which subsequent printings are indicated by the absence of early numerals or letters.

For titles that have never been out of print, a line is included indicating which printing it is, although not including the date.

For books originally published outside of the United States, their original copyright year is stated as well as that of the first American edition.

Philomel Books and G. P. Putnam's Sons, a division of The Putnam & Grosset Group before their acquisition by Penguin Random House, did specify first editions with a code and the words "First Impression for all first editions."

G.P. Putnam's Sons

Since its inception in 1838, G.P. Putnam's Sons has grown into one of the most respected—and controversial—publishing houses in the United States. In 1996, the publishing house became an imprint of the Penguin Group and continues to publish the works of outstanding authors of both fiction and non-fiction.

A Quick History of G.P. Putnam's Sons

George Palmer Putnam and John Wiley entered a partnership in 1838, setting up office in New York City. Three years later, Putnam went to London to set up a branch there, making Putnam the first American publishing company with an office there. When Putnam returned to New York in 1848, he dissolved the partnership with Wiley, who went on to start John Wiley & Sons, which still exists as an independent publisher today. He started G.P. Putnam and Company.

In 1853 Putnam's Monthly Magazine of American Literature, Science and Art was launched with Charles Frederick Briggs as editor. The magazine later merged with Emerson's United States Magazine and again with The Atlantic Monthly. Throughout the latter half of the nineteenth century, the publishing house stayed abreast of trends in America's interests and reading habits.

Founder George P. Putnam passed away in 1872, leaving his heirs to run the firm. They renamed it George P. Putnam's Sons. George H. Putnam took on the role of president, which he held for the next 52 years.

Meanwhile, the second half of the nineteenth century held some interesting milestones for the firm. In 1880, the company accepted a 200,000-word manuscript scrawled in pencil on yellow paper. It was written by 19-year-old Anna Katherine Green. Published as The Leavenworth Case, the book helped establish the genre of the detective novel.

In 1884, Theodore Roosevelt convinced the firm that he was ardently interested in a publishing career and became a special partner. He barraged the firm with mostly absurd proposals. But George P. Putnam's Sons would go on to publish Roosevelt's The Naval War of 1812 and The Winning of the West.

The publishing house brought legendary authors like James Fenimore Cooper, Edgar Allan Poe, Vladimir Nabokov, Joseph Conrad, and Robert A. Heinlein to American readers. Today, as an imprint of Penguin USA, George Putnam's Sons publishes well-known authors like Tom Clancy, Clive Cussler, Patricia Cornwell, Sue Grafton, Amy Tan, and Kurt Vonnegut. The company has had more New York Times bestsellers in fiction and non-fiction than any other publishing house.

Identifying George Putnam's Sons' First Editions

Since 1928, G.P. Putnam's Sons has published several statements regarding the identifications of its first editions in the US and the UK.

G.P. Putnam's Sons, LTD (UK)

1928-1947: First editions are indicated on the title page with the words "First published" followed by the month and year. Later printings have a line underneath saying “Reprinted” along with the month and year. If the content of the book is changed significantly, this will be denoted with the words "Second Edition" on the title page, followed by the month and year.

G.P. Putnam's Sons (US)

1928-1959: The title page does not normally include any entry to indicate first editions. However, in subsequent printings the words “First printed” followed by the relevant dates appear under the copyright notice. Similarly, the other printings and their dates are included. The absence of this note indicates that a book is a first edition. The publishers avoid using the term "second edition" unless there is material difference from the first edition. For major publications that are reprinted annually, the date is omitted from the title page.

1960-1988: All editions other than the first include the words "second (or "third, "fourth,” etc.) impression" on the copyright page. The first edition is not noted.

1989-1992: A sequence of numbers from 1 to 10 appears from left to right on the copyright page (1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10). The last number on the left indicates the printing. Thus if all numbers are present, the book is a first edition. If a Putnam edition has previously been published overseas, it will be identified on the copyright page as the “First American Edition.”

1993-Present: G.P. Putnam's Sons began following the first edition identification conventions of the Putnam & Grosset Group. First editions are not identified except that the copyright page indicates the year of publication. Books that are reprinted include no indication of which printing they are. If a subsequent printing contains new copyrightable material, it will include both the new and the original copyright years. However, some books do include a letter or number code. For example A B C D E F G H would be a first printing. B C D E F G H would be a second printing.

It's important to note that Philomel Books and G.P. Putnam's Sons carry a code in numbers along with the words "First Impression" for all first editions. In later printings these words are deleted, and the lowest number listed indicated the printing.

Random House

Random House is the largest general-interest trade book publisher in the world. The publishing house was founded in 1927 by Americans Bennet Cerf and Donald Klopfer, who had acquired the Modern Library imprint from publisher Horace Liveright two years before. As for the name, Cerf said, "We just said we were going to publish a few books on the side at random," and Random House was born. The company entered reference publishing in 1947 with the American College Dictionary. Random House acquired Alfred A. Knopf, Inc in 1960 and Pantheon Books in 1961.

Private German corporation Bertelsmann purchased Random House in 1998. Now the company has an entertainment arm, Random House Studio, for film and television, along with story content for video games, social networks, the web, and mobile platforms. In October 2012, Random House entered talks with Pearson plc about a merger, and the EU approved the merger without restriction, following the suit of the U.S. Department of Justice and the corresponding organizations in Australia and New Zealand. In 2017, Pearson sold 22% of its stake in Penguin Random House back to Bertelsmann.

Random House First Editions

Random House has issued multiple statements regarding the identification of first editions. Conventions vary for different countries, as well.

Random House, Inc

1928-1935: Random House published only limited editions. Thus, all the necessary information was contained on the colophon because the first edition was the only edition.

1936-1975: For limited editions, all information was still contained on the colophon. Other first editions were plainly marked 'first edition' on the copyright page.

1976-2000: All first editions from Random House, AA Knopf, and Pantheon carry the words "first edition" on the copyright page. Random House also defined these as first printings. In some more recent publications, there may be a number line which in first and second printings begins or ends with a "2". For example, a book with the print number line "23456789" is a first printing with the "first edition" statement present, it is a second printing without the first edition statement present.

2001-present: Random House still follows the 1976 convention, as do Villard and Random House Trade Books. By 2001, Knopf and Pantheon had developed their own guidelines for identifying first editions.

Random House Australia

Random House Australia has issued only one statement, in 2000. The house changed its practices: they added a line that records 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1. They delete the number starting at 1 for the first reprint, so the first edition/first printings are the only ones to have a "1."

Random House Australia Pty Ltd

The words "First published" appear on the imprint page, and "Reprinted..." is added as necessary. The latest statement (2000) reiterated the continuation of this convention.

Random House UK Limited/Random House Group Limited/Random House Business Books (UK)

Starting in 1994, the copyright pages of various imprints were standardized. On the copyright page appears 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2. The "1" is deleted with the first reprint, the "2" for the next, etc.

In 1999, Random House UK Limited changed its name to Random House Group Limited. The convention for identifying first editions was maintained and was also adopted for Random House Business Books.

Random House (NZ) Ltd

The New Zealand branch of Random House stated in 1995 that they have no way of identifying first editions and first printings, except that they do make note of subsequent editions or reprints.

Simon & Schuster

One of the four largest English-language publishing houses, Simon & Schuster now publishes over 2,000 titles a year under 35 different imprints. The firm started by publishing crossword puzzle books and grew to publish some of the world's most recognized authors.

A Puzzling Publisher

In 1913, the first crossword puzzle appeared in the New York World. The diversion was immediately popular. Richard L. Simon's aunt was a fan, and in 1923 she asked her nephew where to buy a book of crossword puzzles. That book didn't yet exist, and Simon decided to capitalize on the opportunity. After all, in previous years, books of Coué (1921), Mah Jong (1922), and Bananas (1923) had hit the market with astonishing success. Simon formed a partnership with M. Lincoln "Max" Schuster to publish crossword puzzle books, and Simon and Schuster was born. The duo decided to attach small pencils to their books as part of their marketing. To this day, Simon and Schuster remains the main publisher of crossword puzzle books.

M. Lincoln "Max" Schuster & Richard "Dick" Simon

The firm continued to innovate. In 1939 Simon and Schuster launched Pocket Books with Robert Fair de Graff. This was the first American publisher of paperback books. And in 1942, Simon & Schuster started Little Golden Books in cooperation with the Artists and Writers Guild. The venture into children's book publishing proved quite successful. Western Printing and Lithography partnered with Simon & Schuster to handle the actual printing, finally buying out Simon and Schuster in 1958.

Legendary Editors

Simon & Schuster's most notable editors-in-chief have been Robert Gottlieb and Michael Korda. Gottlieb joined Simon & Schuster in 1955 as the assistant to Editor-in-Chief Jack Goodman. Gottlieb was the one to discover Joseph Heller and Catch-22. He's edited works by a host of famous names, including Salman Rushdie, John Gardner, Ray Bradbury, and Michael Crichton. It was Gottlieb who famously rejected John Kennedy Toole's first draft of A Confederacy of Dunces. Toole refused to make Gottlieb's suggested changes and later committed suicide. Toole's mother had the book published at the Louisiana State Press, and Toole received a posthumous Pulitzer Prize thanks to the book.

Michael Korda got his start at Simon & Schuster in 1958, as an editorial assistant who waded through the "slush pile." After rising to Editor-in-Chief, Korda published works by Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, William L. Shirer, and Will and Amy Durant. Korda is also a prolific writer in his own right. He's penned novels, memoirs, and non-fiction. Many of his works are histories, but he's explored topics as diverse as the life of Lawrence of Arabia and the hobby of watch collecting.

Expansion and Acquisition

Like most modern publishing houses, Simon & Schuster has seen significant changes in the past several decades:

-

1944: Marshall Field III, owner of the Chicago Sun newspaper, bought both Simon & Schuster and Pocket Books. When Field passed away in 1957, his heirs sold Simon & Schuster back to its original founders, while Leon Shimkin and James M. Jacobson bought Pocket Books.

-

1975: Gulf + Western acquired Simon & Schuster. In 1984, they acquired Prentice Hall, followed by mapmaker Gousha in 1987. Gousha was eventually sold to Rand McNally (1996).

-

1989: Gulf + Western changed its name to Paramount Communications. Three years later, the company was sold to Viacom. Simon & Schuster immediately acquired Prentice Hall and began launching imprints in conjunction with Paramounts MTV Network-owned channels.

-

1998: Viacom sold Simon & Schuster's educational operations to Pearson PLC, which also owns Penguin and Financial Times.

-

2002: Simon & Schuster partnered with General Mills for the Cheerio's Spoonfuls of Stories program. Miniature versions of Simon & Schuster children's books would be included in specially marked boxes of Cheerios.

-

2005: Viacom split into Viacom and CBS Corporation. The latter owns Simon & Schuster, but National Amusements retains majority ownership of both Viacom and CBS. Simon & Schuster still publishes books based on Viacom's properties, which include DreamWorks movies and popular franchises like Mission: Impossible, Star Trek, and CSI.

Identifying First Editions from Simon & Schuster

Over the years, Simon & Schuster has published a wide variety of authors, from political figures like Jimmy Carter and Hillary Clinton, to popular novelists such as Janet Evanovich and Mary Higgins Clark. Thus many rare book collectors need to know how to identify a first edition from Simon & Schuster. Since its inception in 1924, the company has issued multiple statements regarding first edition identification:

1924-1936: First editions are indicated by the lack of printing or edition notice on the copyright page. Subsequent editions include the date and sometimes the quantity of the printing.

1937- 1973: First editions do not include printing or edition notices on the copyright page. Subsequent editions do include the date and sometimes the printing quantity. The date and the words "first printing" are not always used on first editions, but second and subsequent editions are always marked as such.

Mid-1973-1980: Simon & Schuster used a string of numbers on the copyright page to indicate print number. Occasional exceptions are made, in which the words "First Printing" are spelled out on the copyright page. The date may also be included in these cases. In the 1976 statement, the publisher clarified the use of the word "edition," which they used in two ways: 1) to distinguish the binding style, such as when the book is available in both paperback and casebound editions; and 2) to indicate the version of the text. "Edition" therefore does not mean "impression" or "printing." The first number on the copyright page could be a "1," but the title or copyright page shows that the book is a revised or subsequent edition.

1981-present: The same conventions as above were used, with one important exception. Rather than printing the numbers on the copyright page in sequence, they sometimes appeared as "1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2." The lowest number shown indicates the print number.

St. Martin's Press

Headquartered in New York City's iconic Flatiron building, St. Martin's Press is one of the largest publishers of English-language books in the world. The publishing house puts out approximately 700 titles per year under multiple imprints.

Macmillen Publishers of UK founded St. Martin's in 1952, naming it for St. Martin's Lane in London. The house was privately owned until the late 1990s, when it was sold to Holtzbrinck Publishers, LLC. This group of publishers, held by Verlagsgruppe Georg von Holtzbrinck, is a family concern that also owns publishing houses Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Holt Publishers, and Tor-Forge Books.

St. Martin's Press has published some interesting and controversial titles over the years.

St. Martin's Press is known for publishing works by an incredibly wide variety of authors, and they work with a number of bestselling authors such as Dan Brown, Janet Evanovich, and Robert Ludlum. Another claim to fame: St. Martin's Press publishes The New York Times crossword puzzle books.

In 1981, the textbook division, Bedford-St. Martin's, was founded. Three years later, St. Martin's became the first major trade-book publisher to release its hardcover books through its own in-house mass market paperback company. St. Martin's Mass Market Paperback Co, Inc. was founded by Sally Richardson (who remained publisher until early 2018 when she became chairman), with the stewardship of then-President Thomas McCormack.

Collectors of modern first editions frequently encounter books published by St. Martin's Press. While mainstream books and bestsellers are published under the auspices of St. Martin's Press, other genres have been published under St. Martin's Press imprints:

-

St. Martin's Griffin (mainstream paperbacks, including romance and science fiction)

-

Truman Talley Books (specialty and business)

-

Minotaur (thrillers, suspense, and mystery)

-

Thomas Dunne Books (mainstream and suspense)

-

Picador (specialty)

How to Identify First Editions from St Martin's Press and its Imprints

Unlike other publishers, which issue frequent statements about first edition identification, St. Martin's Press offers little guidance.

St. Martin's Press, Incorporated

In a 1976 statement, the publishing house stated that it "rarely [designates] first editions per se." Revised editions of the book may be denoted as subsequent editions, and occasionally the printing will be noted on the copyright page. The next statement, in 1988, noted that there was no change in first edition identification practices.

St. Martin's Press, Australia

Both St. Martin's Press, Australia and Picador, Australia follow the conventions outlined in Pan Macmillan Australia's 1994 statement. First printings are identified with the word "First published (year) in (imprint). Prior to 1994, the group hadn't been denoting the imprint. In 2001, Pan Macmillan Australia added that its imprints are Macmillan, Pan, Picador, and Pancake Press.

Picador (UK)

Picador's first statement regarding first edition identification defers to the conventions of Pan Books Ltd, as do Pavanne, Piccolo, and Piper. Their 1988 statement begins with a reminder that Pan Books largely publishes reprints, and that only approximately 15% of their output was original material. The publisher denoted four different categories of books, each with its own convention:

-

Books first published in Great Britain as hardcover editions bear the words "First printed in (year) by (British publisher)"

-

Books first published elsewhere, then in Great Britain as hardcover editions say "First published in Great Britain in (year) by (British publisher). This edition published (year) by Pan Books Ltd.

-

Books first published outside Great Britain, then by Pan Books Ltd. directly bear the words "First published (elsewhere) (year) by (publisher) This edition first published in Great Britain (year) by Pan Books Ltd.

-

Original works say "First published (year) by Pan Books Ltd.

Following this information are the Pan Books address; numerical indication of impression number; copyright symbol and copyright owner; and the ISBN. Impression number had been noted throughout the publisher's history, but the addition of "2nd printing," "3rd printing," etc began only around 1982. Since then all printings have been indicated with a row of numbers from 9 down to 1, 19 down to 10, and the lowest figure indicates the impression number. A reprint with corrections is also specified if the changes aren't substantial enough to designate the book as a new edition. In 1994, Pan Books Ltd issued another statement, reiterating the conventions followed in 1988.

In 2000, Picador's statement deferred to that of Pan Macmillan (United Kingdom), which in turn adhered to the statements of Macmillan Publishers Limited (United Kingdom).

Macmillan Publishers Limited (UK)

In 1982, Macmillan Publishers Limited stated that "Until 1968/9 our first editions carried the date of publication on the title page." If a new edition was produced or the book was merely reprinted, a statement was added to the back of the title page that says "First edition (year)/Reprinted (year)/Second edition (year)/Reprinted (year)." The latest printing year appeared on the title page.

After about 1968, the date was omitted from the title page and instead the words "First published (year) by (imprint)" appeared on the back of the title page of all first editions. Reprints and new editions bore the words "Published by (imprint)" and a statement similar to that used before 1968 to indicate the book's bibliographic history. During the transitional years of 1968 and 1969, either practice may have been used. Other important points:

-

Books completely lacking bibliographical information or that say on the title page only "First published (year) by (imprint)" are almost undoubtedly first editions.

-

If a book bears the words "First published in (location)" or something similar, it's likely that either earlier or simultaneous publication occurred.

-

It's generally evident when a book has been translated from another language.

-

In the case of joint imprints (usually two associated publishers in different countries), simultaneous publication should be assumed.

-

Where copies of the same edition are bound in both hard and paper covers, they were often but not always published simultaneously. But if the paperback appeared later, the year isn't always noted on the copyright page.

-

Numerous publications have been acquired from elsewhere over the years, namely those of Julius Charles Hare (1856); Lord Tennyson (1884); Richard Bentley (1898); Thomas Hardy (1902); and WB Yeats (1916). Collectors should consult the relevant bibliographies for extensive information.

-

The pre-Macmillan and US editions of Rudyard Kipling (both original and pirated) are well documented.

-

The publication date of Lewis Carroll's Through the Looking Glass is often listed as 1871, though the edition is dated 1872. The actual publication date was December 11, 1871.

In 2000, Macmillan Publishers Limited added that starting in 1996, they had begun the practice of marking printings and reprints with a row of numbers from 1 to 10. First printings had the "1" present in the string. They also added that the following imprints followed these conventions: Macmillan Press Ltd. (UK) (from September 1, 2000 rebranded as Palgrave Publishers Ltd.); Macmillan Children's Books (UK); Pan Macmillan (UK); Pan Macmillan UK imprints; Picador; Boxtree; Sidgwick; and Jackson.

Identifying Book Club Editions

If you collect modern first editions, you have probably encountered Book Club editions pretty frequently. Collectors frequently ask whether Book Club editions are first editions, and whether these volumes have any additional value. Book Club editions are generally differentiated from trade editions, and some people collect specific trade editions.

There are some notable exceptions in which the book club edition may actually be the first edition, such as with Pierre Boulle's La Planète des Singes (The Planet of the Apes), pictured at left, where the true first French edition of the original text is also the book club edition for Le Cercle de nouveau livre. But this is the exception, rather than the rule.

There are some notable exceptions in which the book club edition may actually be the first edition, such as with Pierre Boulle's La Planète des Singes (The Planet of the Apes), pictured at left, where the true first French edition of the original text is also the book club edition for Le Cercle de nouveau livre. But this is the exception, rather than the rule.

Before Book Clubs, Bluestockings

For as long as books have existed, people have gathered to discuss them. These often ad hoc reading groups grew even more prevalent with the invention of the printing press, which brought books to a wider audience. Books were still expensive, so it wasn't uncommon for people to pool their money to buy a book to share. Eventually this trend would evolve into the formation of library societies. In the United States, the first such organization was the New York Society Library (founded in 1754), closely followed by the Boston Library Society. Similar paid libraries popped up around the country over the next century, and some still exist today as literary societies or social organizations.

Meanwhile, in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the literary salon became quite popular. Salons proved an excellent means for women to gain the intellectual stimulation and autonomy they sought. Women would host the events and invite their female friends. Usually a male luminary would be invited to be the guest speaker for the evening. Eventually salons became gatherings for leading socialites, intellegentsia, and politicians. The women who attended earned the nickname "bluestockings," which by 1863 had come to mean "pedantic or ridiculously literary ladies," at least according to the 1863 New American Cyclopedia.

Book Clubs Democratize Education

The first American book club as we think of the groups today was formed in 1877, in Mattoon, Illinois. Unlike the salon, this book club was open to members of the community, regardless of socioeconomic status or educational background. The book club came to be seen as a means of giving the working class access to higher culture and education. Boston's Saturday Evening Girl's Club, founded in 1899, catered to the intellectual needs of working-class women and girls in the city's north end, who usually had little or no access to formal education.

Improvements in printing technology both fueled interest in book clubs and supported it. In the 1870's and 1880's, books were increasingly sold by subscription. And from 1880 to 1900, three times as many books were published as were published before the Civil War. Then the 1920's brought new economic growth, and the book club acted as a sort of doorway to mainstream social progress. The Literary Guild was founded in 1921; the Book-of-the-Month Club in 1926.

Popular Selections with Critical Acclaim

By 1947, there were over three million book-club members in America. That year, the Great Books Foundation was launched by two University of Chicago scholars. Its aim: "the noble work of self-improvement." The Foundation offered guided discussion on canonical texts. Then in 1951, Columbia University professors Lionel Trilling and Jacques Barzun teamed up with celebrated poet WH Auden to start the Readers' Subscription Club, whose purpose was, in the words of Barzun, "to create an audience for books that otehr clubs considered to be too far above the public taste." Thus book clubs had again veered back to the scholarly elite.

But America's level of education was also changing. In 1920, there were 600,000 people enrolled in college. Only thirty years later, that number had ballooned to more than two million. Thus, that lofty goal of democratizing high culture, a popular ideal of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, had essentially been attained. A correlation of national bestsellers, book club selections, and critically acclaimed literature indicates that more and more book clubs were in fact choosing "high brow" books.

Today, thanks to the internet, book clubs can meet both in person and online. It's difficult to count exactly how many people participate in them. For collectors, the designation of "Book Club edition" can be a confusing one.

How to Identify Book Club Editions

A book club edition may or may not be a special edition issued just for members, and it's usually not the first edition. Thus, the books don't generally garner much interest among serious collectors. But they can be terrific reading copies or a great place to start for new collectors who are interested in modern first editions.

It's not uncommon for a book club edition to be marked as a first edition or first printing--because it could indeed be the first printing of the book club edition, but not the first printing of the trade edition. So collectors must track down identifying marks for the first trade edition and compare it to the book club edition.

How to Identify Book of the Month Club Editions

Since it was founded in 1926, the Book of the Month Club has been incredibly popular. The club offers its members several selections each month, and these generally include a few books from frequently collected authors. These points can be used to identify Book of the Month Club editions, along with editions from a few other book clubs.

- Book of the Month Club books usually bear a small square, circle, or other geometric shape on the lower right-hand corner of the back cover. In the past that mark was printed on the cover cloth, and later it was debossed (indented).

- In the gutter of the last few pages of the book, there's often an alphanumeric sequence printed in Book of the Month Club books.

- The dust jacket may bear some reference to the Book of the Month Club (or other book club). This reference often appears on the top or bottom of the front or back of the dust jacket flap. Meanwhile, book club editions often have no price printed on the dust jacket, unlike trade editions.

- Book of the Month Club books usually lack headbands, which are the small decorative band (usually made of cloth) that are fastened inside the top and sometimes inside the bottom of the book's spine. Book of the Month Club books are also not generally stained or colored on the top edges of the pages.

- Trade editions often use heavier paper and cover stock than book club editions do, so book club editions often feel lighter than trade editions.

Identification Statements from Specific Book Clubs

In most cases, book clubs simply buy trade editions from a publisher's general run and resell them to members without altering the books or their jackets in any way. This means that book club editions are the same as trade editions. They can be identified as first editions simply by consulting the publisher's statements for first edition identification. In other cases, book clubs are large enough to make changes to the books.

- The Episcopal Book Club: From 1980 to 1984, trade editions were used for book club editions. They still bore the publisher's prices on the dust jackets. They also usually had a club emblem and corporate name inside the dust jackets. These may also have occurred on the front cover, along with the words "Selection of the Episcopal Book Club."

- The Fraggle Rock Book Club: In a 1988 statement, the Fraggle Rock Book Club issued a statement that Weekly Reader books were identified on the back cover, the spine, and the copyright page. They also lacked an ISBN and a retail price. These book club editions are also a different size and printed with a different paper stock than the trade editions. The Muppet Babies and Weekly Reader Book Clubs followed the same convention.

- Guideposts: In 1988, Guideposts issued a statement that most Book Club and Book Service selections bear a cross enclosed in a circle on the book's spine and on the dust jacket. The Guideposts registered name and "Carmel, New York 10512" are frequently printed on the back of the dust jacket.

- The Artists Book Club LTD (United Kingdom): According to the 1988 statement, the Artists Book Club did not have special editions from suppliers, but rather bought publishers remainders if the book was a new title, or publisher's stock for backlist items. Nothing would distinguish the Book Club editions from the trade editions. If the quantity ordered is sufficient to warrant the extra cost (that is, at least 1,500 copies), the Book Club colophon appears on the jacket spine and possibly on the spine of the binding; and the Book Club name appears on the title page where the publisher's name normally appears. The Book Club name also sometimes appears on the verso of the title page with a separate ISBN number.

First Books vs. First Editions: The Difference and the Significance

Everyone thinks they understand the value of a first edition. The first printing of a book automatically makes it rare, right? Because X or Y novel is a first run, it’s immediately valuable and worthy of collecting, yes? While this is certainly the case with a number of books throughout the literary landscape, first editions are not necessarily sought after by collectors just because they’re the first run. In fact, when you think about it, every book ever published has a first edition printing, but some were not lucky enough to see a second or third.

One factor that truly makes a book rare, valuable, and the apple of a collector’s eye is the combination of a first edition and a first book—that is, the first printing of an author’s first novel, usually an author of great regard or with a long, profound literary career. These literary Easter eggs are usually printed in small quantities—remember: we’re talking about first novels from predominantly debut authors—and are often hardcover and ornate or individualized in cover design as subsequent printings tend to reduce artistic quality for mass reproduction. By the time these authors publish their second, third, or fourth books, first print runs usually increase based on demand, which makes the first editions of these first novels even more rare and valuable.

It’s an interesting confluence of elements—the right book, the right author, the right time. But for serious and novice book collectors alike, the first edition of first books represent something of a white whale when it comes to rarity and value. To help illustrate the importance of first editions of first books, here are four first books whose first editions are considered top-tier finds for book collectors the world over.

Casino Royale

Ian Fleming published his debut James Bond novel in April 1953 to rave reviews and brisk sales. The first printing of the novel consisted of about 4,000 copies and the novel sold through its first printing in less than one month; though many of these first edition copies were sent to libraries across England, a 1955 paperback release of the novel sold more than 41,000 copies in one year. Casino Royale was the first of Fleming’s 12 Bond novels. For collectors, the sheer feat of acquiring a first edition of Casino Royale should not be understated. It is arguably one of the most highly-collectible Bond novels, and copies in good condition can range in value from $10,000 to $100,000, not including special inscriptions or other markings. Since Fleming’s death in 1964, eight other authors have continued the Bond series through novels and novelizations of the 007 film series, though none have captured audiences quite like Fleming’s original tales.

Ian Fleming published his debut James Bond novel in April 1953 to rave reviews and brisk sales. The first printing of the novel consisted of about 4,000 copies and the novel sold through its first printing in less than one month; though many of these first edition copies were sent to libraries across England, a 1955 paperback release of the novel sold more than 41,000 copies in one year. Casino Royale was the first of Fleming’s 12 Bond novels. For collectors, the sheer feat of acquiring a first edition of Casino Royale should not be understated. It is arguably one of the most highly-collectible Bond novels, and copies in good condition can range in value from $10,000 to $100,000, not including special inscriptions or other markings. Since Fleming’s death in 1964, eight other authors have continued the Bond series through novels and novelizations of the 007 film series, though none have captured audiences quite like Fleming’s original tales.

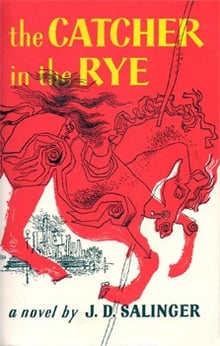

Catcher in the Rye

More than 60 years on from its publication, J.D, Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye continues to be the prototypical novel for the lost, disenfranchised, and wayward youth of America. The story of Holden Caulfield and his angst-ridden exploits through New York City and beyond are read by more than 1 million people each year worldwide, with total sales reaching nearly 65 million books across the globe. Though Salinger famously became a recluse following the publication and public reaction to the novel, he published a handful of other book-length works during his life, most notably the short story collection, Nine Stories (1953). His debut novel remains his most popular and widely read, and first editions in pristine condition often fetch more than $40,000 in online and brick-and-mortar auction settings.

More than 60 years on from its publication, J.D, Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye continues to be the prototypical novel for the lost, disenfranchised, and wayward youth of America. The story of Holden Caulfield and his angst-ridden exploits through New York City and beyond are read by more than 1 million people each year worldwide, with total sales reaching nearly 65 million books across the globe. Though Salinger famously became a recluse following the publication and public reaction to the novel, he published a handful of other book-length works during his life, most notably the short story collection, Nine Stories (1953). His debut novel remains his most popular and widely read, and first editions in pristine condition often fetch more than $40,000 in online and brick-and-mortar auction settings.

Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone

It may be hard to believe given the fervor with which author J.K. Rowling’s boy wizard Harry Potter took the literary world by storm, but Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, the first in the Potter series, only saw a U.K. first edition run of 500 copies. Released in 1997, roughly 300 of these copies were distributed to libraries, leaving even fewer copies for purchase on the open market. Most, if not all, of these first U.K. editions are now in the hands of collectors and are considered one of the more prized titles for collection in recent literary history, particularly due to the title change when the novel was reprinted for American audiences—publishers believed a novel with the word ‘philosopher’ in the title would be a hard sell for U.S. readers. Depending on condition, prices for first U.K. editions of the Philosopher’s Stone can range from $40,000 to $55,000.

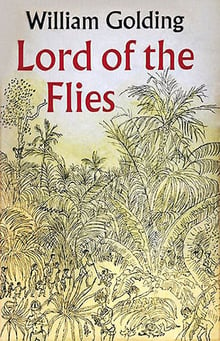

Lord of the Flies

William Golding’s 1954 novel often finds itself on lists of banned books across the globe for its portrait of chaos, disorder, and cruelty amongst the novel’s young central characters; however, some argue the novel’s shocking storyline—at least shocking for 1954—helped propel the book to bestseller status across the globe. The novel has since been translated into dozens of languages, sold millions of copies worldwide, and helped Golding win a Nobel Prize for Literature in 1983. While Golding continued to write long after the publication of his debut novel, no piece of writing achieved the success or acclaim of Lord of Flies, making first editions extremely valuable to collectors. Copies in good condition can fetch more than $30,000 in auction settings worldwide.

William Golding’s 1954 novel often finds itself on lists of banned books across the globe for its portrait of chaos, disorder, and cruelty amongst the novel’s young central characters; however, some argue the novel’s shocking storyline—at least shocking for 1954—helped propel the book to bestseller status across the globe. The novel has since been translated into dozens of languages, sold millions of copies worldwide, and helped Golding win a Nobel Prize for Literature in 1983. While Golding continued to write long after the publication of his debut novel, no piece of writing achieved the success or acclaim of Lord of Flies, making first editions extremely valuable to collectors. Copies in good condition can fetch more than $30,000 in auction settings worldwide.